2022 | Film 14 MIN. | English

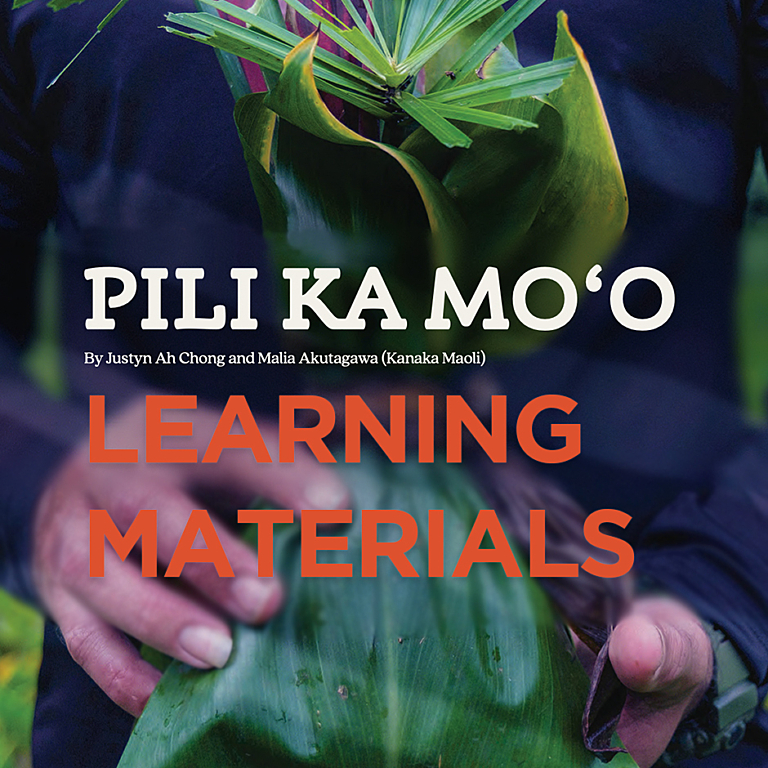

Pili Ka Moʻo

Justyn Ah Chong with Malia Akutagawa (Kanaka Maoli)

The Fukumitsu ʻOhana (family) of Hakipuʻu are Native Hawaiian taro farmers and keepers of this generational practice. While much of Oʻahu has become urbanized, Hakipuʻu remains a kīpuka (oasis) of traditional knowledge where great chiefs once resided and their bones still remain. The Fukumitsus are tossed into a world of complex real estate and judicial proceedings when nearby Kualoa Ranch, a large settler-owned corporation, destroys their familial burials to make way for continued development plans.

See the making of video here.

LEARNING MATERIALS & DOWNLOADS

“It seems that now more than ever, Native Hawaiian burials are being dug up and ancestral remains disturbed for the sake of continued "development," "progress," and economic gain here in the occupied Hawaiian Kingdom. By highlighting the Fukumitsu family and their ongoing struggle to protect their ‘iwi kūpuna (family burials), we hope this film sheds light on the reciprocal relationship Native Hawaiians maintain with their family beyond the veil, and allows others to see why for us, it isn’t simply old bones in the ground, but rather treasures worth protecting at all costs.” - Justyn and Malia

While Indigenous cultures worldwide are highly diverse and not monolithic, reciprocity is a common core value that typically constructs relationships of respect between the living and their ancestors. In Kānaka ‘Ōiwi culture, the ancestors whose bones infuse the land are known as iwi kūpuna, and as is common in virtually all cultures around the world, their burials are regarded with deep reverence.

Due to the ongoing relentless development in the islands by powerful foreign interests, the land and its original people are under increasing pressure in a variety of ways. In Pili Ka Mo‘o, we see how protecting ancient Kānaka burials is connected to the integrity of ecosystems, in this case through the farming of taro. In Hawaiian mo‘olelo (stories), taro originates as the stillborn child of Wākea and Ho‘ohōkūkalani, making the fight for Hakipu‘u — a traditional land district that long predates colonization — even more deeply connected to iwi kūpuna. Ninety-five percent (95%) of the Fukumitsu family’s homeland, Hakipu‘u, is owned by foreigners, primarily the Kualoa Ranch, which has recently acquired more land that contains precious family burials down the road from where the family resides.

The origins of this settler colonial conflict has its roots in the 1800s, when descendants of missionary families came to own and control all of the sugar cane production in Hawai‘i. The cultivation of sugar displaced Native Hawaiians from their land, diverted water from naturally flowing streams used for taro cultivation, and brought hundreds of thousands of poorly-paid agricultural laborers from Japan, China, the Philippines, Korea, Portugal, and elsewhere.

Many of these people eventually came to call Hawai‘i home and joined their lives with Native Hawaiians. A unique local culture was birthed out of all of these relationships during the plantation era. Thus, many people in Hawai‘i today are a mixture of ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

The imposition of western private property regimes onto Hawaiian lands means that property rights take precedence over Kānaka claims to land and their ability to maintain their culture. The colonial structure of the state of Hawai‘i means that traditional Kānaka burials are not accorded the same respect as those of foreign settlers.

- Why do you think Hawaiian burial grounds are treated differently by some people than burials in settler cemeteries?

- Kōlea and Summer’s child was asked to recite the names of his ancestors in the tradition of chanting (called oli) in the Hawaiian language. How did you feel when the child began to recite the names?

- What is the significance of Kōlea walking the ‘āina (land) and moving the soil and mud away to free up the spring? Is there a larger meaning here for you and for all of us?

- In the film, Malia Akutagawa says: "If you cannot protect the land, forget it. And if you cannot protect the ancestors, to help us return to ourselves, then we lose everything. To unearth our kūpuna in the ground, we cannot have our own ancestors rest peacefully." What is your interpretation of Malia’s words?

- The filmmakers are guided by love and responsibility for their ‘ohana (family) and this extends to their ancestors and the future generations in a reciprocal relationship that crosses generations in the physical and non-physical realms. What comes up for you when you consider this?

Find additional discussion questions in the downloadable learning materials on this page.

- Education Incubator: Invitation with Aloha https://eduincubator.org/our-stories/Noho Hewa:

- The Wrongful Occupation of Hawai’i https://nohohewa.com/

- David Aiona Chang, The World and All the Things Upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration

- Protect Hakipu’u

- For more background about Kōlea, Summer, and their family, see EPS 1: Naholowa’a Mo’olelo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_vp4DyQQAc

- Aloha Rising - Hakipu’u ‘Āina Aloha https://www.facebook.com/officeofhawaiianaffairs/videos/3285002934949370/

- Listen to Kōlea and Summer at 11:08

- Listen to Malia Akutagawa at 19:04

- Documentaries About Remembrance and Cultural Celebration in the 2022 BlackStar Film Festival

August 3, 2022 - HYPERALLERGIC - Environmental Film Festival Australia Celebrates Indigenous Perspectives with Sovereign Cinema

November 18, 2022 - The Curb - Why We Should Listen to Indigenous Voices About the Climate Crisis

November 23, 2022 - The Takeaway - WYNC Studios

Making of Videos & Trailer

Behind the scenes

Fukumitsu ‘ohana overlook the land

Kalo farmer Kolea Fukumitsu works the loʻi on generational family land.

Kolea Fukumitsu prepares a Hoʻokupu (gift offering) on camera

Portrait of Native Hawaiian Reciprocity Project collaborators Malia Akutagawa and Justyn Ah Chong at Hakipuʻu, Oʻahu

Kolea Fukumitsu shows a harvested kalo to the camera.

A Hoʻokupu (gift offering) beautifully prepared with intention and prayer

November 23, 2022

The Takeaway - WYNC Studios

Why We Should Listen to Indigenous Voices About the Climate Crisis

Read articleAugust 3, 2022

HYPERALLERGIC

Documentaries About Remembrance and Cultural Celebration in the 2022 BlackStar Film Festival

Read articleNovember 18, 2022

The Curb

Environmental Film Festival Australia Celebrates Indigenous Perspectives with Sovereign Cinema

Read articleCritical acclaim for this film

“To unearth our kupuna in the ground is like the final eviction,” a quote from the film, lingers in my mind as a fellow Native Hawaiian. It is a reminder that the spiritual war featured in PILI KA MO`O clearly ties back to the Colonization of Hawai’i and the dark side of Capitalism.

– Ciara Lacy